What are the steps to completing a successful animation? Obviously, it takes a lot of time, skill, planning, and plain expertise. The animation pipeline is a detailed game plan for your project. When considering the ‘animation pipeline’, you should have a good idea as to what step of your project you’re on.

The main steps of the animation pipeline are things like concept, designs, storyboard, layouts, music, poses, and outline. All of these things during your project make up the animation pipeline. Think of a factory, with all of its different steps along the way to make a product from its raw materials to its finished final product.

The raw materials, in this case, are daring ideas, good artistry, a bold execution, and a polished final product.

Concept

The most basic step of the art pipeline, the very concept of your current project is the lifeblood of your creation. This step is the foundation of what you will eventually create and submit. This is also the step of the process where ideas matter.

This is time to pitch that specific idea you had for a game or animation, as everyone will be brainstorming with each other, and maybe that idea you had would be perfect for the project. Imagine best animation studios like Disney—characters like the Genie from Aladdin and Scar from the Lion King—were all birthed in talented concept-planning sessions.

These are the bones of the animation production pipeline and the game art pipeline.

The only limitation you have during this process is that you need to be aware that you’re working within the confines of the technology in use. Your ideas may be great and ambitious, but they need to fit into the technology that you will eventually ship your product with.

Not everything comes easy to everyone; even the big studios like Rockstar and Bungie go through all the same struggles and processes that make an idea into a tangible product, the culmination of all of your hard work. Games like Grand Theft Auto V and Red Dead Redemption II must have gone through hundreds of hours of just throwing ideas around between the writers’ room alone.

Rob Nelson, co-head of Rockstar North, discussed the challenges and ideas he and his team in Scotland had when addressing the improvements, they could and should deal with when moving from 2010’s Red Dead Redemption to the prequel, while keeping things fresh and making them new and shiny:

“We made the decision, at least the group that I worked with, to delve into the old game again and try to discern what the essence of it was, the feeling of it. The feeling that people came away with, I think, was the feeling of being able to exist in a wilderness and to survive. To just be.

That was the thing that ultimately — along with the story and the tone of the game — that resonated with people…When we looked at it, it was quite limited.

You could kill everything and “skin” it, but all you did with those things was sell them…we took those ideas and ensured that, even though now we’ve decided to tell the story of being in this game, and living and working in this game, we still wanted you to be able to go out and exist in the wilderness, to be alone, to have space, to survive off the land.

Hunting and crafting and camping and exploring, all of those things, were things we needed to take to a new level, because they felt like they were there before. We wanted to really make sure they were there this time.”

Rob Nelson and his team seemingly had it made: they had a game, a foundation in which to work that many would kill for in the industry. However, it seemed as if the concept alone was almost an insurmountable task, taking what is known and loved and developing for players that are now 8 years removed from the original title.

This first step of the process is universal when it comes to production pipelines; it’s just the degree to which the developers are working. Whether it’s the most famous game developers ever or an indie studio with just one artist, each company or group must ensure their concept is robust and free from cracks to succeed on the game art pipeline.

Design

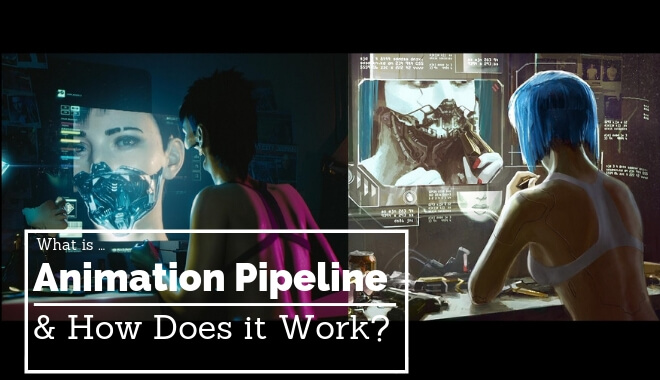

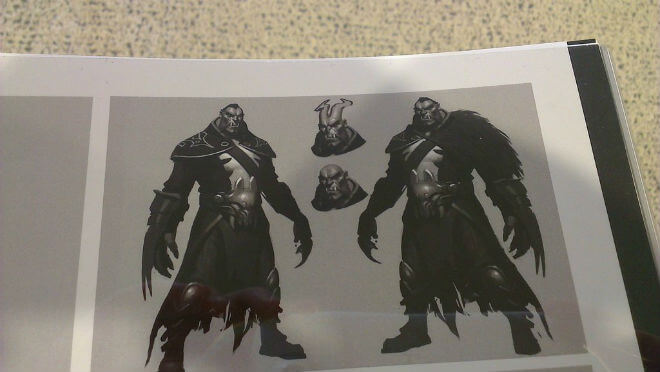

Now, this is where everything that has been planned comes to life, more or less. Those brave ideas thrown around during the brainstorming sessions are now put to paper, or through programs. With video games, teams of artists are employed to draw the concept art for some of our favorite characters, their behavior, and their very essence, breathing life into them.

Some studios, specifically with indie studios, may only have one artist available to them, making the daunting task of making a world come to life before our eyes are even more staggering.

I like this stage specifically because everyone is working together as a unit. Each person is a valuable asset to the team, and even though there may be disagreement and strife, each part works together and the absence of some could be fatal to the project.

This is when the animation team will utilize programs like Photoshop, GIMP, and Flash. This is also when textures and animations are put into place. What kind of world do you want your characters to inhabit? What do enemies look like? How do the two engage with one another in your game world?

All of these, (addressed through storyboards and ideas), are key parts of the design process. Harnessing the power of editing and drawing software, developers can harness the power of the concept laid out earlier and make them real. Pipeline art, however, is still in its infancy.

This is the preparation for the pre-production phase, in which all of the aforementioned actions are all pooled into place, ready to begin to execute.

Pre-Production

Preparations for the process of doing the work are now set. The animation pipeline is now on the move. Along with the standard video game artist in the company lies another, newer type. Enter the technical artist.

This middle-man of artists seems to be integral to the process, and I’m glad that they’re becoming the new norm.

A lot of miscommunication can occur, (like with most things), while actually putting the animation programs into use, and the technical artist is there to make sure there’s a healthy line of communication between the different parties that matter. Their job is to make sure not only is everything running smoothly, but that their work is in line with everyone else’s.

This employee must wear many different hats: artistic skills, as well as technical skills, are necessary. They go as far as choosing the best art program for a company to use for their product. It seems that the technical artist is really a modern Renaissance Person, taking on many responsibilities and executing them with style, grace, and skill.

The game art pipeline keeps running smoothly due to technical artists and allows other employees to divert their workload into different categories to make sure everything is running smoothly.

Top game companies hire technical artists, and it’s a good thing too: imagine the thousands of artists on Red Dead Redemption II being on a different page from writers and a director like Rob Nelson. It would be a nightmare. Thankfully, they’re there to make sure nothing gets lost in the cracks.

This is also when things start to come together in a more recognizable way. The project’s alpha is usually released as a rudimentary build. You may be familiar with Steam’s ‘Early Access’ Games.

These are games that are currently being developed, still in their alpha stage, and they’re able to be played by the gaming community, having the gamers’ purchases of the access to funding the developer’s further production. A personal favorite of mine, Rust, was put on Early Access in 2014. It was an ambitious aim: a free-roam survival game.

I absolutely loved it in all of its different builds. It recently got a full release nearly four years later. That may seem like a long time, but the production pipeline must be moving in tandem with all of the developers, using the valuable feedback from their users to better the game and make sure that it releases in its best possible state at the time.

Garry Newman, the developer, warned people not to get their hopes up that this will be a huge celebration when the game launches regularly. He says:

“Part of leaving Early Access is making the development more stable”, explained Newman, “That means that not rushing in features and fixes that end up breaking something else.” To that end, the developer will be transitioning from a weekly update schedule to a monthly one, with a stable Main Branch in place for monthly updates and irregular hotfixes…”

Even after their long tenure in Early Access, Rust is still getting close attention paid to it, something I’m definitely grateful for. Newman hopes that the game isn’t a letdown and thanks to the players for helping them develop the most stable version of their game. The players actually take part in the animation pipeline, becoming unofficial game developers themselves.

Their ability to communicate closely with developers makes both parties great innovators and make games better.

However, sometimes the alpha process can be strewn with problems and, ultimately, fail. We hate to see things like this happen, but when the communication that I’ve outlined doesn’t go according to plan, the absence of competent technical artists, a giant rift between creative vision and execution, and perhaps even lack of funds can scuttle a game onto the shores of failure.

Specifically, the Early Access game Spacebase DF-9 by the gaming company Double Fine, ultimately failed the Early Access phase overall due to a hasty release to the general public. Their Early Access was going normally until the developers decided to release the game prematurely in comparison with the dev team’s aims of regular updates.

The result was a lackluster effort where a lot of features weren’t present. At first, the developers were committed to keeping tweaking the game after its release with a combination of Steam Workshop content and patches. However, Tim Schafer, Double Fine’s lead, cut off that idea by stating that Early Access profits weren’t able to cover the costs and it would be more trouble than it was worth.

As you can see, pre-production can mean the life or death of a project. The Rust team took the best possible avenue: they listened to their player base, they engaged with all communities, and stayed dedicated to the project no matter what. It seems with Double Fine’s predicament, it was a big case of miscommunication and lack of funds.

While on production pipelines, some projects hit the ultimate snag on this one, and it’s a shame. Think on how many great projects we would’ve been able to see and experience if everyone was on the same page, and projects received enough funding. Dean Hall had a clear, concise statement on his project, DayZ:

“I hope I implement a lot of bad ideas… So that then, we know they are bad. Then we can remove them and move on… If we stick to safe ideas, this isn’t going to become a great game over the next few months – it will just be a cool idea and I’ll try and spend the next ten years going around conventions talking about how cool it was. I’d rather follow all the dead ends, so I know what works and what doesn’t.”

—Dean Hall, lead designer of DayZ

Post-production

Now things are actually being put to the test. This is when the project is near completion. Game testers are brought in to test out the alpha, (if not on Steam Early Access), actually get paid to play, (how cool is that), and tell the developer about the experience and other things like glitches. Game testing seems like a sweet deal: you could make thousands of dollars doing it.

Sure, you’d probably be in a more technical than a recreational state of mind, on the hunt for bugs and glitches, but being paid to play games is my idea of fun.

The developers can then release their project through open or closed beta, either giving access to their project to everyone or only a select few. Beta test cycles can last anywhere from a short amount of time, like a few weeks, or even a few years.

It all depends on the complexity of the software and technology, what you need to change, and of course, the people playing or viewing your beta. I wish I could put down a definite timeline, but everything is different in this case. Some developers may release their product into beta as more of a ‘preview’ than an actual process of seriously fixing what could be wrong with the media.

Currently, the mobile Elder Scrolls: Blades open beta is from June 11th, 2018, and ending March 2019. In contrast, you have the open beta of Warhammer: Vermintide 2 that is only a month long. It all depends on what these two developers think needs to be done. Maybe Bethesda wants the mobile experience of the Elder Scrolls to be robust and made perfect.

The developers of Vermintide 2 could already have everything figured out and maybe need just a little more opinion or ironing out the kinks until they’re confident of their release.

This phase is the final phase of the production pipeline, eventually leading to your project being released wherever it intends to go. Hopefully, your ideas and your dedication will lead to amazing successes like Garry Newman’s Rust, Rob Nelson’s Red Dead Redemption II, and avoid blunders like Double Fine’s Spacebase DF-9.